Parsing Algorithm¶

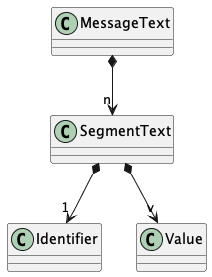

An exchange-format X12 EDI message is a sequence of segments. Each segment has an identifier of 2 or 3 characters, followed by the element values. The elements are separated by an element separator, and the segments are separated by a segment separator.

We can depict it as follows:

For example, the following segment uses “|” as an element separator and “~” as a segment separator.

ST|271|0001~

This segment can be viewed as three string values, “ST”, “271”, and “0001”. The first string value is the segment identifier.

Alternatively, this segment can be viewed as an identifier and separator, “ST|”, followed by two string values, “271” and “0001”.

We generally choose the former view, which permits simple use of the fields = string.split()

to split the segment into fields.

The first field (fields[0]) is the identifier, used for parsing the structure of a message and the loops.

The remaining values (fields[1:]) are assigned to elements and composites of the segment.

General Parsing¶

There’s a subtlety to the separators.

Important

The separator characters are defined in the ISA segment.

This means we have to read the ISA segment to figure out what separators define the structure of the ISA segment.

The are two relevant conventions that seem to break the circularity of parsing the ISA to find the punctuation required to parse the ISA segment.

The last three characters of the ISA segment will have the three punctuation marks. The final element of this segment is the component separator character. This will have an element separator in front of it and the segment separator after it.

The ISA segment is generally uncompressed, and is 106 characters long. With an uncompressed ISA, the relevant values are here:

Position 103: Element separator in front of the final element.

Position 104: “Component” separator. This is one character of data. It is used when an element is really an array of values. It varies widely based on the text values actually present in the message.

Position 105: Segment separator. Is the end of every segment.

If the ISA is compressed, then we don’t know where it ends and what the segment separator is. Then we have two fallback strategies:

Hope for line break whitespace, and consume the last 3 characters of a line that starts with

"ISA".Eyeball the data, figure out what the segment separator is, and provide this “manually.” The element separator is position 3. The component separaror is the 16th element. (Yucky, but, sometimes necessary.)

Often, the source of the message traffic will provide some hint as to what the format really is.

An enterprise may adopt a convention of naming messages something.edi to show that the ISA segment is uncompressed

and the first line is helpful. A name like something.medi might should that the ISA segment is

compressed and separate metadata is required to identify the separators. Perhaps a something-meta.toml file

could be used to convey the necessary separator information.

Message Parsing¶

Pragmatically, message parsing is made complicated the following feature:

Loops are not present in the text representation. There’s no identifier or punctuation for loops. A Loop contains one or more Segments, defining an expected sequence of Segments.

This means we have the following relationships.

The essential algorithm works by consuming each segment based on the defined loops within a message. A source lexical scanner “peeks” at the heading of the next segment. The Loop parser then use the heading to decide if it should consume the next Segment or if it is finished consuming Segments.

Consuming a Segment means locating the Elements and Composites (sequences of Elements) within the segment, and assigning text values to those elements and composites. This is slightly different from consuming segments because there are fewer choices to be made.

Segment Parsing¶

Conceptually, the Segment parsing algorithm uses approach similar to the following:

identifier, *fields = segment_text.split(element_separator)

segment_class[identifier].build_attrs(fields)

Elements are not actually atomic. This means a value separated by element separators can contain component separator characters. It can be decomposed into a list of values.

fields = [

val.split(component_separator) if component_separator in val else val

for val in fields

]

An important consequence is the Component Separator must be provided separately in the ISA16. Further, it can be unique for each message. This avoids having to escape the component separator when it occurs in a value.

It appears that the software encoding a message must pick a component separator character based on the values present in those (few) fields that can have sub-components in them.

The default seems to be “:”.

But, if there’s a “:” character in a field’s value, the component separator might be “^” or “\”.