The back-story. See Coping With Complexity. See https://github.com/cloud-custodian/cel-python for the code base.

I've reached the point where progress is clearly impossible. A bad decision a few weeks ago has reached it's inevitable conclusion. I've made a terrible mistake. About 1,000 lines of code -- and tons of time debugging -- are all wasted.

Or, were they?

BLUF (TL;DR)

We make mistakes.

Generally, "mistake" is a synonym for "learning". A mistake is a lesson in what not to do.

We can't avoid mistakes. Instead, we have to learn as much as possible from them.

(What about people who "don't learn from their mistakes"? They really do learn. They also refuse to change their behavior in a way that avoids making substantially similar mistakes again. They often modify their behavior to avoid a few unpleasant aspects of a recent mistake while continuing to make related mistakes.)

Mistakes don't have a cost. They are an investment.

Context

This is part of Cloud Custodian (C7N), to permit writing simpler logical expressions in more conventional notation. See https://cloudcustodian.io/docs/filters.html for information on the YAML-based filter notation. It's very sophisticated. But, sometimes hard to read.

Container

This runs in the lambda or other server context as part of Custodian. It's not a separate process in a separate container. It's an importable package that extends C7N's filter to include additional syntax.

Component

See https://github.com/cloud-custodian/cel-python for the code base.

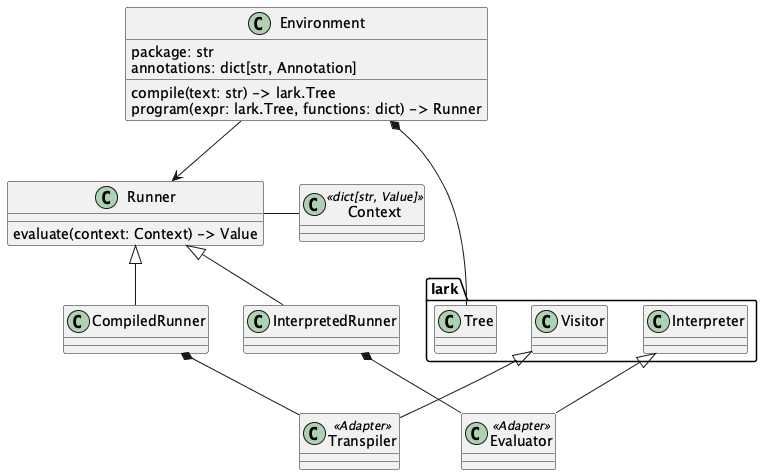

We were looking at implementing the following conceptual model. Until we found the counter-example.

A notional design overview of some of the classes for CEL Python. This has problems, it turns out.

The application will create an Environment. It uses this to compile a CEL expression, and then create a Runner to evaluate the expression. (This lets you cache the Runner to reuse it.)

The Runner evaluates the expression in a Context where variables, functions, and type definitions are found. While the Context type is shown as a name for a Python dict[str, Value], it could be a protobuf message with all the stuff in it.

We're adding the new subclasses of Runner:

- The InterpretedRunner uses a subclass of lark.Interpreter to interpret the AST and compute a final value.

- The CompiledRunner uses a subclass of lark.Visitor to transpile the AST into Python. The Pythonic transpilation output is compiled, and the built-in exec() function computes a final value from this. This runs at native Python speeds, and avoids the overhead of visiting AST nodes.

Code

Let's not go there. This is about design decisions.

What's Wrong

In retrospect, it's clear -- perfectly and abundantly clear -- that the presence of CEL macros is a non-trivial feature.

CEL has some_object.map(x, some_expression_with_x) as a construct.

Syntactically, it looks like a .map() method of some_object. The presence of a bind variable, x, and an expression where x is a free variable suggests this is not simply a method. This is nothing like the expression some_string.startsWith('hello'): a method with an argument value that can be immediately evaluated and produce a result.

CEL calls it a "macro" because it's really a higher-level construct. It's visually indistinguishable from a function, but it's semantically unrelated.

In Python, the syntax for this is (some_expression_with_x for x in some_object) or map(lambda x: some_expressions_with_x, some_object). The bind variable and expression have a distinctive syntax that makes them easy to work with.

CEL lacks a distinctive syntax. Sigh. For me, the function-like syntax was an attractive nuisance.

Okay, There are Macros

The Lark Visitor is "bottom-up". It visits leaf nodes and then higher and higher level nodes.

This means 6 * 7 will visit the following nodes:

- Leaf node with literal 6. Nothing much to transpiling this into Python.

- Leaf node with literal 7. Also, really easy to transpile into Python.

- Multiplication node with two leaf nodes and an operator, *. Also. Easy to transpile. A template of "{left} * {right}" works nicely. Or, maybe "operator.mul({left}, {right})".

This simple design is inadequate for macro processing.

Consider this: ['foal', 'foo', 'four'].exists_one(n, n.startsWith('fo')).

How is this visited?

The left-hand side:

- Leaf node with literal 'foal'.

- Leaf node with literal 'foo'.

- Leaf node with literal 'four'.

- An "expression list" node to assemble the three literals.

- A "list literal" node built from the expression list.

The right-hand side:

- The n variable. Warning: This is not a sub-expression

- The 'fo' literal.

- An "expression list" node to build the one literal as a single-element list.

- The "dot ident arg" node with startsWith as the identifier, and the expression list node.

- The n variable. Again.

- A complete n.startsWith('fo') primary expression. At this point, it's not clear that n is a bind variable that doesn't have a value in the default activation.

- An "expression list" node to build n, and the n.startsWith('fo') expression as a list. RED ALERT: This is not a list of expressions. This a bind variable name and an expression.

The final expression as a whole:

A "dot ident arg" node with exists_one as the identifier, and the expression list node. This can't work because the exists_one is a macro that needs a bind variable and sub-expression. It needs to bind multiple values to the bind variable and evaluate the sub-expression for each value.

Note that an expression n (See Warning, above) and an expression list n, n.startsWith('fo') (see RED ALERT, above) are not really part of this, but, well, they were visited and generated transpiled code.

We wind up with some extra, irrelevant, transpiled code floating around in our internal data structures.

Ugh.

Bottom up is inappropriate when handling macros. The subsidiary parts -- the bind variable and the sub-expression -- need special handling.

The Lark Visitor is doesn't fit perfectly with the approach required for Transpiling. Stuff is visited that appears to be a useful sub-expression. But. It's not simply a sub-expression that can be evaluated and passed up the parse tree to compute a final answer.

First, the n sub-expression only makes sense in the context of a macro binding a value to it. It's not an expression at all. It's an identifier.

Second, the sub-expression with the n variable buried in it can't be evaluated outside the macro context.

Every other expression can be trivially evaluated and the result passed up the parse tree.

The Duh Factor

The InterpretedRunner extended the lark.Interpreter class.

At first blush, it seemed like transpiling might be different. We might be able to --- trivially --- rewrite the code from CEL to Python using the lark.Visitor.

After getting to a regression test failure, it is clear that we cannot trivially transpile a macro into Python. The simplistic lark.Visitor design doesn't work.

But Wait...

The nuance here is that the transpiled pieces and parts -- in isolation -- actually are useful. We need to to avoid trivially conflating object.method(arg), which has a simple value, with object.macro(variable, expression), generates more complicated code.

This seems to be a two-pass operation.

Phase I. A Visitor walks the parse tree and decorates AST nodes with a Python string transpilation of the node.

- Literals get the Pythonic version of the CEL literal as a string.

- Identifiers become an "activation.{name}: string.

- Operators, functions, and methods all get normalized to a template that pulls in the children strings to create a complete Python expression string.

- If all the children are strings, then the template can be transformed into a string and treated as if it were a simple literal. For example, the "{left} * {right}" template can be filled in right away with two literals.

- If any of the children are templates, short-circuits, or macros, the final creation of code has to wait for Phase II.

- The short-circuit logic operators, _&&_, _||_, and _?_:_ at this level are complicated templates. It's slightly easier to defer filling them until Phase II because they build multiple lines of code.

- The macros (distinct from methods) require Phase II processing.

Phase II. A second Visitor walks the parse tree, looking for the already completed decorations on AST nodes, and the templates to be completed.

Any unfilled templates require visiting the children, substituting them into the template, and updating the decoration from template to string. These become simple lambdas.

expr_{n} = lambda activation: {operator_template(*children)}

Each child will be a single blob of text, built up from numerous children involving ordinary literals and operators. The resulting expression string used to decorate the parse tree is "expr_{n}", where n is some unique number.

Short-circuit operators are expanded into lambdas that may or may not raise exceptions that may or may not be ignored. true || 42 / 0 is true. No exception is raised.

ex_{n}_left = lambda activation: True ex_{n}_right = lambda activation: 42 // 0 expr_{n} = lambda activation: logical_or_function(activation, ex_left, ex_right)

The logical_or_function will evaluate sub-expressions and silence exceptions as needed.

And yes, everything is a lambda, even the literals. It makes life simpler.

The resulting expression string used to decorate the parse tree is "expr_{n}", where n is some unique number.

Which brings us to macros. Example: ['foal', 'foo', 'four'].exists_one(n, n.startsWith('fo')). The left-hand side is an ordinary sub-expression. For Python's purposes, this object will be used by a generator expression to create sub-activations with the bind variable set.

ex_{n}_left = lambda activation: ['foal', 'foo', 'four'] activation_gen = (activation.nested_activation(vars=dict({bind variable}=_value)) for _value in ex_{n}_left)

Or, we could use map(lambda a: a.nested_activation(vars=dict({bind variable}=_value)), ex_{n}_left).

Now, we can evaluate the macro.

ex_{n}_right = lambda sub_activation: startsWith(sub_activation.n, 'fo') expr_{n} = lambda activation: 1 == sum(1 for _is_true in map(ex_right, activation_gen(activation)) if _is_true)

This resulting block of code, while bulky, captures the macro processing. Each of the macros has a unique expression structure, but they're all based on the built-in map(). In this case, CEL exists_one(...) is an assertion that there was one result.

And, like everything else, the resulting expression string used to decorate the parse tree is "expr_{n}", where n is some unique number.

What's important here is that we use a lark Visitor for this, not an Interpreter.

What's The Distinction?

The Lark Visitor always visits the children first. The results of the child visit are then available for the parent to use. The generic lark.Visitor class can be decorated with types for parameters and results to clarify how the evaluation works.

The approach is good for everything but macros. The literal nodes roll up into the primary nodes that roll up into various priorities of expression nodes. The final, top-most expr node can be an amalgamation of all the visited children. Operations are properly nested by the AST definitions of relation, addition, and multiplication grammar productions.

The Lark Interpreter doesn't visit the children automatically. The application methods must explicitly call visit() or visit_children() as needed. When interpreting the AST to evaluate it, this is an annoying detail until we get to macros. For macros, it's imperative to not trivially visit the children. See the Warning and RED ALERT, above.

For evaluation, processing must work like this. First, evaluate the left-hand side to get an object. The first child of the macro node has the bind variable. For each value in the object, create a sub-activation with the bind variable; then, visit only the second child of the macro node to get a value. This limited use of visiting children makes it easy to implement interpretation of a macro.

The same kind of processing can apply to transpiling a macro into Python. Or. As shown above, we can do two passes:

- the easy non-macro transpilation,

- macro transpilation, which doesn't trivially roll the children up into the parent.

The Cost of the Mistake

Mistakes don't have a cost.

This is a fallacy. A big one. One that cripples technical management.

Mistakes are an investment in learning.

In this case, it's about 1,000 lines of code that will be reworked.

It took hours to create and debug the code I'm about to delete.

It will take hours to replace them with something that

- Actually works.

- Has a simple example that absolutely requires the more sophisticated design.

- (Note that I didn't have this until a specific regression test failed.)

- Benefits from the the incorrect version, and working examples of the various kinds of lambda templates.

The final point is really important and under-valued:

Refactoring is Easier than Initial Development

Folks have an unwarranted fear of refactoring and the "cost" of rework.

Could I Have Prevented This?

The dream of methodology designers everywhere is to placate managers with an approach this will avoid this investment.

The dream is to be able to make this claim:

"Follow my method and you won't waste time digging in some rat-hole right up to a dead end."

What's nonsensical about this is that there needs to be some level of actual thinking going on.

It's nonsense because someone has to deeply understand this problem, and leverage that understanding to avoid writing bad code. Someone has to put in hours understanding the problem to avoid the code.

What form does this detailed "understanding" take?

Clearly, the waterfall dream claim was a "detailed design document."

And this document was based on what, exactly?

- Staring at a whiteboard?

- Expensive multi-person meetings?

- Long, expensive, pointless conversations with an hallucinating AI tool. (Watch 2001: A Space Odyssey for more on hallucination-prone AI tools.)

Or, is the detailed design document based on draft code that demonstrates a problem? The design-level draft is used to create a design document. Which is then used to create final code.

In the olden days this was considered a non-starter. Code was expensive. Those days are past. Draft code is part of the process.