Data Validation Mode¶

We validate applications and files both share a schema through a three-tier process.

Validate application’s use of a schema via conventional unit testing. This is part of the previous Schema-Based Access Validation demo.

Validate file conformance to a schema via “live-file testing”. This is part of the previous Schema-Based Access Validation demo.

Validate the three-way application-schema-file binding by including a Data Validation command or optional mode in every file processing application.

In this section we’ll show how to include a Data Validation sub-command in every file processing application.

Having a validation sub-command means that we must disentangle all of the persistent state change operations from the input and processing in our application. The “normal” mode makes persistent changes to files or databases. The “validation” mode doesn’t make persistent changes. The validation mode can be viewed as a sort of “dry run”: all the processing with none of the writing.

We’ll do this with a combination of the Command and the Strategy design patterns.

We’ll create applications which validate their input file and have a simple plug-in strategy for doing any final persistent processing on that file.

See the demo/app.py file in the Git repository for the complete source.

Note

Simple File Structures

This demo app is designed to work with simple files with an embedded schema. An assumption is that the relevant sheets within a workbook have a consistent structure, often called First Normal Form. (No repeating groups, all values are atomic.)

Design Patterns¶

There are two central design patterns that allow an application to have a validation (or “dry-run”) mode that avoid destructive writes:

Using the Command design pattern to isolate state changes from other processing.

Use a Context Manager so the behavior of commands is controlled by the context.

We’ll start with the Command design pattern.

State Change Commands¶

The Command design patterns is helpful for isolating state changes in an application.

Each state change (create, update, delete) should be built as a Command class, with an option to be disabled it. In validate mode, these state changing commands are disabled. In “normal” processing mode, these commands are enabled.

Here are some examples:

For Extract-Transform-Load (ETL) applications, the state-changing commands are database loads or file writes.

For create-retrieve-update-delete (CRUD) programs, the state-changing commands are the variations on create, update and delete. The retrieves don’t make state changes.

For data warehouse dimensional conformance applications, a state change may implement a slowly-changing dimension (SCD) algorithm. This would that do inserts or updates (or both) into a dimension table.

For applications that involve a a multi-step workflow with (potentially) several state changes along the way, each change is a command.

In some cases, a fairly sophisticated Command class hierarchy is called for. In other cases, there’s only one (or a very few) statement commands.

Once we’ve broken the work down into Command instances, we need to use a Context to make sure the state changes are enabled or disabled consistently. We’ll look at the context manager next.

Persistence Context Manager¶

One good way to distinguish between persistent and transient processing is to use a Strategy class hierarchy. This will have two variations on the persistent state changes:

Process. This subclass actually makes persistent state changes.

Validate. This subclass avoids persistent state changes.

This follows the Liskov Substitution Principle of the SOLID design principles. It assures that either of these subclasses can be replacements for an abstract base class.

Combining the validate Strategy with the state change Command leads to class similar to the following example. This superclass defines methods to implement the persistent processing. This is the “normal” mode that makes proper changes to the filesystem or database.

class Persistent_Processing:

stop_on_exception = True

def __init__(self, target: Union[DB, IO, Whatever]) -> None:

self.target = target

self.file_or_database: Union[DB, IO, Whatever]

def save_this(self, this: This) -> None:

this.serialize(self.file_or_database)

def save_that(self, that: That -> None):

that.serialize(self.file_or_database)

Next, we’ll add the methods needed make this a context manager. This is a polite way to support any preparation or finalization. For example, we would use the context manager to create database connections, or finalize file system operations, etc.

def __enter__(self) -> "Persistent_Processing":

self.file_or_database = file_or_database.open(self.target)

return self

def __exit__(

self,

exc_type: Optional[Type[BaseException]],

exc_val: Optional[BaseException],

exc_tb: TracebackType

) -> None:

if self.file_or_database:

self.file_or_database.close()

Here’s a subclass that offers the safe, do-nothing strategy. This is used for “validate-mode” processing:

class Validate_Only_Processing(Persistent_Processing):

stop_on_exception = False

def __init__(self, target: Union[DB, IO, Whatever]) -> None:

super().__init__(target)

def __enter__(self) -> "Persistent_Processing":

self.file_or_database = None

return self

def save_this(self, this: This) -> None:

pass

def save_that(self, that: That) -> None:

pass

An Alternate Design¶

We could take a slightly different approach to this design. We could make validation mode the superclass. The subclass could then add the persistence features.

This doesn’t actually work out well in practice.

Why not?

It’s often too easy to overlook important details when trying to create the validation mode superclass. The normal persistent processing subclass can then end up having a lot of extra stuff added to it.

The idea is to have the minimal change between these two versions.

The design winds up somewhat better looking if we write the complete version including persistence as the superclass. We can then factor out the state-changing steps to create a subclass variant of the command.

Having these two classes allows us to configure our application processing at run-time.

Example Application¶

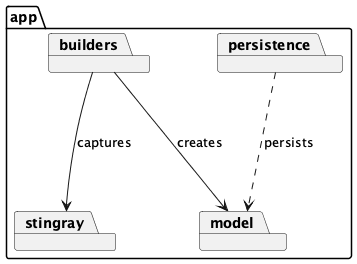

We’ll decompose the application into a number of separate areas.

We’ll start with the core application model.

Model Components¶

The central model objects embody the useful state and processing of our application. We want to strip away considerations of data capture and validation. We also want to strip away details of persistence.

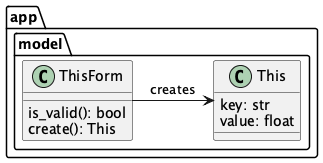

Here’s a model object, This, and it’s form, ThisForm.

@dataclass

class This:

key: str

value: float

def serialize(self, file: TextIO) -> None:

return asdict(self)

def other_app_method(self) -> None:

pass

The application-specific processing for this class is the vague other_app_method() method.

For some kinds of applications, there can be a great deal of application unique processing.

For other applications, there’s little more than serialization to help transfer a representation of the object’s state to a file or database.

We’ve borrowed the concept of a Form from the Django project.

The Form is used for input validation.

We use a generic dict[str, Any] as the source of data for a form.

This corresponds with the way HTML form input or query strings arrive in a web application.

It is also relatively easy to serialize for multiprocessing applications.

An alternative is to follow the Pydantic design pattern and include validation in the class definition.

Here’s the “form” associated with our This class:

class ThisForm:

def __init__(self, **kw: Any) -> None:

self.clean = kw

def is_valid(self) -> bool:

return all(

[

self.clean["key"] is not None,

self.clean["value"] is not None,

]

)

def create(self) -> This:

return This(**self.clean)

The idea here is to build application objects with a two-step dance.

A builder function uses a schema to transform a source

Rowobject into adict[str, Any]intermediate.The

ThisFormclass validates the intermediate dictionary. I will only createThisinstances when the dictionary’s data is valid.The

Thisobject is the essential processing for the application, and acan be serialized for persistence.

The reason for this decomposition is to make sure the application is insulated from changes to input sources and the resulting schema changes.

When working with spreadsheets, schema changes are a constant source of struggle and conspicuous problems. Isolating these details makes the schema problems more observable and resulting changes have a more constrained impact on the application.

We’ll look at an implementation of the persistence context manager next.

Persistence Context Manager¶

We need to be sure that all state changing operations are part of a persistence processing Strategy object. The implementation varies with the kinds of persistence:

File System writes. Generally, these are easy factor into separate methods. This has to broadly include file creates and filesystem operations like directory creation. These depend on the

ioandpathlibmodules.Direct database Create-Update-Delete operations. These operations will involve the database connection object. They can be isolated so the database requests are in separate methods.

Indirect database operations mediated by an Object-Relational Mapping (ORM) layer. While this is bundled into the application model, this can be a little easier to isolate by creating “do nothing” database engine or interface within the ORM framework.

We have two classes to define our two modes: normal operations and validation-only. The superclass defines the normal processing mode: we actually save objects.

class Persistent_Processing:

stop_on_exception = True

def __init__(self, target: TextIO) -> None:

self.target = target

self.file_or_database: TextIO

def save_this(self, this: This) -> None:

self.file_or_database.write(f"{this.serialize()!r}\n")

def __enter__(self) -> "Persistent_Processing":

self.file_or_database = self.target.open("a")

return self

def __exit__(

self,

exc_type: Optional[type[BaseException]],

exc_val: Optional[BaseException],

exc_tb: TracebackType,

) -> None:

if self.file_or_database:

self.file_or_database.close()

The subclass defines validation-only mode: we don’t save anything.

class Validate_Only_Processing(Persistent_Processing):

stop_on_exception = False

def save_this(self, this: This) -> None:

pass

def __enter__(self) -> "Persistent_Processing":

self.file_or_database = None

return self

In this case a single save_this() method needs to be changed.

In larger and more sophisticated applications, there may be many individual methods to enable or disable persistence.

Builder Functions¶

To capture data based on a schema, it helps to have a “builder function”.

This transforms the source Row instances created from a workbook into a form our application can use.

As noted earlier, the builder creates a dict[str, Any] structure that is used by form classes to create instances of the useful application objects.

To handle variant logical layouts, a number of builder functions are provided to map the logical schemata to a more standardized conceptual schema.

def builder_1(row: Row) -> dict[str, Any]:

return dict(

key=row['Column "3" - string'].value(), value=row["Col 2.0 - float"].value()

)

def builder_2(row: Row) -> dict[str, Any]:

return dict(key=row["Column 3"].value(), value=row["Column 2"].value())

Note that these builder functions are frequently added to. It’s rare to get these down to a single version that always works. Instead, each change to input documents will lead to yet another builder function.

It’s important to always add new builder functions. Logical layouts are a moving target. Old layouts don’t go away; modifying a builder is a bad idea. This follows the Open-Closed Principle of the SOLID design principles. The application is open to extension by adding new builders. It’s closed to modification because we won’t change an existing builder, instead we’ll move forward and extend the app with a replacement.

As an optimization we can create the Form objects directly from the row. It’s not clear that this optimization is deeply beneficial. It’s best to start with separate classes and if the processing around these transient dictionaries is a performance problem, then the optimization is helpful.

It helps to have a function like this to map argument values to a builder function.

Builder_Func = Callable[[Row], dict[str, Any]]

def builder_factory(args: argparse.Namespace) -> Builder_Func:

return {"1": builder_1, "2": builder_2}[args.layout]

We can update the mapping to add new builders to the application.

It can help to have a better naming convention that “builder_1” and “builder_2”. In practice, however, it’s sometimes hard to determine why a logical layout changed, making it hard to assign a meaningful name to the layout.

Sheet Processing¶

The Row instances are part of a Sheet collection.

A “sheet process function” captures data from the source sheet, processing the individual rows.

A process_sheet() function is the heart of the application.

This handles all the rows present in a given sheet.

def process_sheet(

builder: Builder_Func, sheet: Sheet, persistence: Persistent_Processing

) -> Counter:

counts = Counter()

for source_row in sheet.rows():

try:

counts["read"] += 1

row_dict = builder(source_row)

row_form = ThisForm(**row_dict)

if row_form.is_valid():

counts["processed"] += 1

this = row_form.create()

persistence.save_this(this)

else:

counts["invalid"] += 1

except Exception as e:

summary = f"{e.__class__.__name__} {e.args!r}"

logger.error(summary)

counts["error", summary] += 1

if persistence.stop_on_exception:

raise

return counts

The objective here is to provide some observability and audit support in addition to row processing. The production of counts acts as confirmation that all rows were handled.

If the counts do not add up properly, the inconsistency demonstrates the presence of programming logic problems. In the even of an unhandled exception, the counts can help locate the row that caused the problem.

Some applications will have variant processing for workbooks that contain different types of sheets.

This leads to different process_this_sheet() and process_that_sheet() functions.

Each will follow this design pattern to process all rows of the sheet.

Workbook Processing¶

The sheet (or sheets) are contained within a workbook. Stingray makes the workbook a common Facade over workbook files as well as COBOL files.

For newline-delimited JSON, CSV, and flat files, a workbook only has a single “sheet.” For other workbooks, there may be multiple sheets; often only one has data and the others are empty.

def process_workbook(

builder: Builder_Func, workbook: Workbook, mode: Persistent_Processing

) -> None:

for sheet in workbook.sheet_iter():

logger.info(f"{workbook.name} :: {sheet.name}")

sheet.set_schema_loader(HeadingRowSchemaLoader())

counts = process_sheet(builder, sheet, mode)

logger.info(pprint.pformat(dict(counts)))

In rare cases, this processing is more complex. For example, a workbook may have multiple sheets, some of which must be ignored.

When we do live-file testing of a given file, we can do something like the following.

This uses validate() to assure that the file’s schema is correct.

Command-Line Interface¶

We have some standard arguments. While we’d like to use “-v” for validate mode, this gets confused with setting the verbosity level.

def parse_args(argv: list[str]) -> argparse.Namespace:

parser = argparse.ArgumentParser()

parser.add_argument("file", type=Path, nargs="+")

parser.add_argument("-o", "--output", type=Path)

parser.add_argument("-d", "--dry-run", default=False, action="store_true")

parser.add_argument("-l", "--layout", default="1", choices=("1", "2"))

parser.add_argument(

"-v",

"--verbose",

dest="verbosity",

default=logging.INFO,

action="store_const",

const=logging.DEBUG,

)

return parser.parse_args(argv)

The overall main() function looks something like the following example.

It handles a number of common main-program issues.

Logging.

Parameter Parsing. This includes interpreting options.

Argument Processing. This means looping over the positional arguments.

Opening Workbooks. Some applications can’t use the default

workbook.Opener. A subclass ofworkbook.Opener, or more complex logic, may be required.Gracefully catching and logging exceptions.

Exit Status to the OS.

def main(argv: list[str] = sys.argv[1:]) -> None:

args = parse_args(argv)

logger.setLevel(args.verbosity)

builder_func = builder_factory(args)

mode_class = Validate_Only_Processing if args.dry_run else Persistent_Processing

logger.info("Mode: {0}".format(mode_class.__name__))

try:

with mode_class(args.output) as mode:

for input in args.file:

with open_workbook(input) as source:

process_workbook(builder_func, source, mode)

except Exception as e:

logger.exception(e)

raise

The highlighted line makes the selection of the persistence class to use, assinging the object to mode_class.

This encapsulates the run-time behavior change for data validation separate from data processing.

Since there are no other relevant programming changes, we can be confident that unit testing will produce a robust application that can be used for data validation without questions or complications.

This leaves a tiny “main program switch” at the end of the module.

if __name__ == "__main__":

logging.basicConfig(stream=sys.stderr)

main()

logging.shutdown()

We strongly discourage a main program switch with any more code in it than shown above.

Running the Demo¶

We can run this program like this.

python demo/app.py -d -l 1 sample/*.csv

This will apply builder with layout 1 against all of the sample/*.csv files.

The output will cinlude look like this

INFO:__main__:Mode: Validate_Only_Processing

INFO:__main__:sample/Anscombe_quartet_data.csv ::

ERROR:__main__:KeyError ('Column "3" - string',)

ERROR:__main__:KeyError ('Column "3" - string',)

ERROR:__main__:KeyError ('Column "3" - string',)

ERROR:__main__:KeyError ('Column "3" - string',)

ERROR:__main__:KeyError ('Column "3" - string',)

ERROR:__main__:KeyError ('Column "3" - string',)

ERROR:__main__:KeyError ('Column "3" - string',)

ERROR:__main__:KeyError ('Column "3" - string',)

ERROR:__main__:KeyError ('Column "3" - string',)

ERROR:__main__:KeyError ('Column "3" - string',)

ERROR:__main__:KeyError ('Column "3" - string',)

INFO:__main__:{'read': 11, ('error', 'KeyError (\'Column "3" - string\',)'): 11}

INFO:__main__:sample/Anscombe_schema.csv ::

ERROR:__main__:KeyError ('Column "3" - string',)

ERROR:__main__:KeyError ('Column "3" - string',)

ERROR:__main__:KeyError ('Column "3" - string',)

ERROR:__main__:KeyError ('Column "3" - string',)

ERROR:__main__:KeyError ('Column "3" - string',)

INFO:__main__:{'read': 5, ('error', 'KeyError (\'Column "3" - string\',)'): 5}

INFO:__main__:sample/csv_workbook.csv ::

INFO:__main__:{'processed': 2, 'read': 2}

INFO:__main__:sample/simple.csv ::

ERROR:__main__:KeyError ('Column "3" - string',)

ERROR:__main__:KeyError ('Column "3" - string',)

ERROR:__main__:KeyError ('Column "3" - string',)

ERROR:__main__:KeyError ('Column "3" - string',)

ERROR:__main__:KeyError ('Column "3" - string',)

ERROR:__main__:KeyError ('Column "3" - string',)

ERROR:__main__:KeyError ('Column "3" - string',)

INFO:__main__:{'read': 7, ('error', 'KeyError (\'Column "3" - string\',)'): 7}

Four separate CSV files were examined.

sample/Anscombe_quartet_data.csvhas eleven rows, all of which are missing the required value.sample/Anscombe_schema.csvhas five rows, all of which are missing the required value.sample/csv_workbook.csvhas two valid rows.sample/simple.csvhas seven rows, all invalid.

When all the rows are wrong, the schema in the file doesn’t match the schema required by the application.

We can – confidently – run the application on the sample/csv_workbook.csv knowing that the file has been tested as well as the application software.